Restorative Justice in Northeast Syria

published 9 March 2022 last modified 11 March 2022

Introduction

I want to start this off with a thought experiment. Imagine that, for one reason or another, state authorities retreated from your area. For all intents and purposes the government was just gone one day. How would you organize your community?

Keep that in the back of your mind as we go.

At time of writing, the way of life most of us have practiced our entire lives seems to be slowly falling the fuck apart. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage and is about to see yet another wave. This is despite three separate readily available vaccines and the incredibly mild inconvenience of wearing a mask in public indoor spaces — but profound distrust in our national media environment has all but shattered any shared conception of truth we might once have operated from. Seizing on this (and arguably causing it) a long simmering proto-fascist movement is right on the verge of boiling over. Lest we stop to breathe for even a second, it turns out the looming threat of climate change is already much further along than most of us hoped. And amidst all that, a sizable chunk of us — those fortunate enough to survive (so far) the invisible spectre of coronavirus — are also facing serious challenges to our material condition, from poverty or houselessness to ailing health and collective trauma. There is next to no social safety net and no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. Collapse — real collapse — has never felt so tangible, or so imminent.

But it’s not all bad news. In the last year and a half we have also seen the largest popular uprising to agitate for social justice in U.S. history, certainly within our lifetimes. Real progress has been made building networks of solidarity on levels local, nationwide, and international. Despite the valiant efforts of culture warlords, grifters, and law enforcement agencies, working and lower middle class Americans now oppose the structural violence of systemic racism at a scale not seen since the 1960s. More Americans than ever have started looking critically at our nation’s history of colonialism and begun imagining paths toward justice. Worldwide, since 2018 a second wave of popular progressive protest movements have kicked off from Hong Kong to Catalonia, following the spate of Arab Spring and Occupy protests of the early 2010s and the racial and environmental justice movements across North America in places like Ferguson, Baltimore, Sherman Park, Unist’ot’en, and Standing Rock.

Revolution is in the air, and it could not be needed more urgently.

This article is part of a campaign for prison abolition being organized across the U.S. As we apply ourselves to the unenviable task of imagining better worlds, it behooves us to put serious thought into designing restorative and transformative justice systems. These would be based not around a desire to seek retribution on the guilty but to restore communities and transform systems of oppression. A significant quandary is that of how we get to such a system from the one we have now.

The broad question I want to consider here is the same one I started with. How would you organize your community after the government pulled away? It’s a big ask, but this scenario grows more important to consider with every broken annual heat or wildfire record. It does not have any one answer and we should be instantly suspicious of the charlatan who claims to have one. We can only approach this question together, imperfectly, with major trial and error. But it helps enormously that we are far from the first to think of it.

We have a lot to learn from two Indigenous-led coalitions who have already built quasi-stateless societies elsewhere in the world. Millions of people live out their lives under autonomous administrations in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, and the region of northeast Syria known to the Kurds as Rojava. Both societies have fascinating justice systems with significant overlap in the way they are structured. This is not quite on purpose, but it is also not at all a coincidence. Later in this series we’ll also look at the role education and social ethics play in cultivating restorative justice, and lay out a case for why, when we try to build a new world in the crumbling shell of the old, Indigenous traditions around justice should be our collective guidestar.

Disclaimer

Before we go on I want to be very clear about who I am — and who I’m not. I am not an expert, let alone a thought leader. I’m here because I have useful skills in research and education, but a lot of the things I’m about to describe are entirely outside my lived experience. While I am not straightforwardly male (or straight) I was born into a body with white skin and a penis. What’s more, a Ph.D. in astrophysics has trained me to deliver words to an audience with far more confidence and authority than I’ve ever actually earned.

Because of these limitations, I’ve sought help from people who actually have experienced the restorative justice systems we’re about to discuss. We’ll hear more from them later in this series; right now I want you to grok that these folx are here to share advice in their own words. We are, of course, fortunate to have their time and attention. But I would also invite you to the idea that — for reasons we will get into later — we cannot merely listen as a passive academic exercise. Their willingness to talk is extremely practical, and extremely symbiotic. What they give to us in knowledge and experience is undoubtedly a gift, but it is also a seed. What we can give to them in return is to sow that seed — as praxis, right here in our own community.

Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria [AANES]

Understanding the cultural revolution in Rojava requires historical context. A fully honest discussion would probably start with European imperialism, World War I, and the Sykes-Picot Agreement, but we don’t have time for all that today. The short version is that in 1916 some French and British assholes secretly drew lines on a map and partitioned the former Ottoman Empire into a mishmash of states with hard borders, casually disregarding centuries of cultural variation across the entire subcontinent. (Incidentally, American audiences unfamiliar with this history should keep Sykes-Picot in mind whenever they wonder why the SWANA region is so geopolitically unstable.)

One people particularly affected by this history are the Kurds, whose traditions, languages, and religions all stretch back thousands of years. The area historically occupied by Kurds, a mountainous region in western Asia known broadly as Kurdistan, was broken up between the states of Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria. I highlight the importance of states and borders to this story because, like the Indigenous nations of North America, these constructs are completely at odds with the way Kurds have lived on this land for literal millenia. Some of the oldest surviving religions in the world are Kurdish. But the modern Kurdish diaspora is balkanized. Kurdish nationalists in Iran advocate for a state of their own; other Kurdish groups in Iraq and Syria have formed separate, de facto autonomous governments. And while the last century has seen the Kurds on both the giving and receiving end of incredible violence, the overall tally is wildly asymmetric. Violence and genocide against Kurds is the norm just as it is with many peoples native to Anatolia.

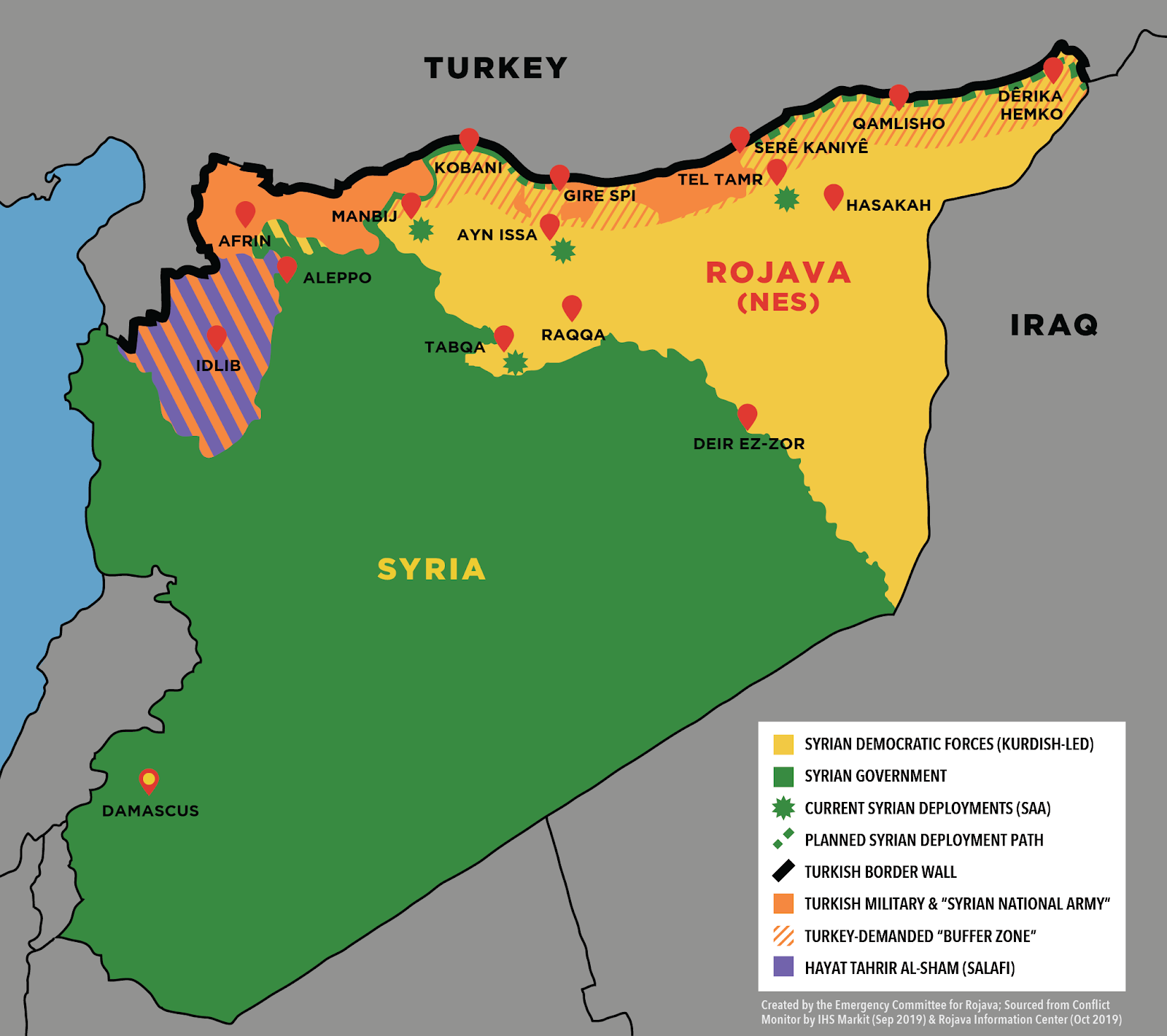

Rojava’s autonomy was realized in the early years of the Syrian Civil War, between 2011 and 2014. In the span of a few short years, a Kurdish militia known as the People’s Protection Units (YPG) successfully fended off the Syrian army. They secured cities throughout the north including Qamişlo, Kobanî, Amûdê, and Efrîn. As fighting intensified towards Aleppo to the west, the Assad regime pulled out across the northeast, effectively ceding partial control to the YPG with relatively little conflict and few casualties. In the areas they captured, the YPG helped set up local municipal councils to manage self-governance and day-to-day affairs. Bit by bit these direct popular assemblies formed a functioning grassroots democracy, and in mid 2014 the first formal Constitution of Rojava had been approved, establishing the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

Since that time, the YPG have forged a coalition with other autonomous militia groups under the umbrella of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). These include the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), an all-women regiment who are the international face of a radical and fundamental cultural shift in this part of Syria. The system of self-government practiced here is called democratic confederalism. It is founded not only on principles you might expect such as autonomy and self-determination, but also on egalitarianism, gender equity, and ecological balance. It holds that every form of oppression is based on that of women by men, and that women’s liberation is therefore necessary for everyone’s well-being. Leadership structures across Rojava, including all local councils, education boards, and self-defence forces, mandate no less than 44% representation from women at all times. The new field of jiniology (from the Kurmanji word jin meaning “woman”) provides women-only spaces to reinterpret all of history, philosophy, politics, art, and science from the perspective of women. And local councils establish cooperative communities to which women can escape from abusive or violent situations and find economic empowerment.

Liberation of women is utterly fundamental to the revolution in Rojava. This is especially evident in the administration’s public education system, which broadly emphasizes students’ autonomy in shaping their curriculum. Like geographical borders, rigid intellectual borders between subjects like science, philosophy, and history are seen as artificial. Classrooms here are a lot more fluid with topics flowing openly into one another, leaving students with a much more dynamic understanding of the world around them. The goal of an education in Rojava is not to train a person how to work, but to enrich themselves and their community.

Rojava’s justice system is equally fascinating. From a writeup in Just Security:

When stability in Syria first dissolved in 2012, the inhabitants of northeastern Syria attempted a level of democratic self-governance without the acquiescence of the Syrian government. The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES), or Rojava as it is known in Syria, has been the de facto government in that region since 2012. Rojava has a constitution and a legal system that notably features a ban on the death penalty, female judges, a ban on extradition to death penalty countries like Iraq, and creative restorative justice. The courts have already tried thousands of Syrian ISIS suspects.

Now, Rojava does have prisons and it does have a functional analog to cops. But both these institutions serve a radically different purpose than their U.S. counterparts. Like most things in Rojava, the Internal Security Forces (Asayîş) are decentralized and autonomous. Asayîş officers who respond in a particular community tend to be members of that community. They also do not have a monopoly on legitimate use of violence; alternatives exist as municipal Civilian Defense Forces and regional Self-Defense Forces. All of these groups answer to the municipal councils which are ultimately composed of community members. From a detailed analysis on the (now archived) website Peace in Kurdistan:

The point of the revolution, many people told us, is not to replace one government with another, it is to end the rule of the state. The question, the co-president of the Kurdish National Congress put it, is “how to rule not with power but against power”. State power is being dispersed in a number of ways. The education of people as Asayish is taking place on a large scale, with the aspiration that everyone will receive it. It is part of an attempt to diffuse the means of coercion to everybody. People’s self-defense, we were told, is “so important that it can’t be delegated”. Through education (not only in the use of weapons but also in mediation, ethics, the history of Kurdistan, imperialism, the psychological war waged by popular culture and the importance of education and self-critique), the fighter in charge of one training centre told us, the aim is to finally abolish Asayish all together.

Security forces in Rojava also actively engage with jiniology. The Asayîş have not only adopted the standard male-female co-president structure, but also formed a separate branch to deal specifically with gender-based violence. The Asayîşa Jin are entirely made up of women who deal with women’s general safety, family disputes against women, and women’s protection during public celebrations and protests. Interviews with Western journalists will often involve a mediator from this branch whose role is to act as a security blanket, encouraging women to share traumatic experiences while reminding the journalists that consent can be revoked at any time.

At the neighborhood level, unarmed local grandmothers are often first responders to community problems. Their role is to facilitate peace after major disruptions, especially acts of emotional or physical violence. They don’t consider a case to be solved until a public truce is agreed to by all parties involved. Reaching a truce can take months and is cause for celebration in a kind of neighborhood feast. This helps ensure public accountability: if any party violates the truce, the entire neighborhood will know.

And this brings us to the wider criminal justice system in Rojava. The democratic confederalist approach to justice provides Peace and Consensus Committees at the neighborhood, municipal, and regional levels. These committees attempt to resolve both criminal and social justice issues by treating them like community problems. The goal of the justice system is not to punish offenders, but to sustain peace through consensus and reconciliation. Rather than inflict harsh punishment, a mediated dialogue takes place in which the accused must come to understand any injustice or damage they’ve caused. Per a descriptive analysis in Capitalism Nature Socialism:

In some cases, compensation is paid to the affected party, and in other cases religion plays an important role in seeking forgiveness. If consensus is not reached on the communal level, the matter is taken to the Peace and Consensus Committee on the neighborhood level. The structure and proceedings of the committee are essentially the same as on the communal level and settling the case through consensus is once again the primary objective. The Peace and Consensus Committees are not authorized to imprison people.

Human rights violations, murder cases, and any others that can’t be resolved by the Peace and Consensus Committees get escalated up to courts. Judges presiding over people’s courts at the city and regional level can be nominated either by a special justice commission (a product of municipal or regional assemblies) or by any person who lives in that area. There are also four appellate judges at the regional level and a final court for each canton (which is roughly analogous to a U.S. state). Responding to criticisms that this structure is too similar to Western hierarchical courts, the administration organized regional Justice Platforms as an alternative to the people’s courts:

The Justice Platforms can be described as larger Peace and Consensus Committees, consisting of up to 300 people from related communes and civil society organizations. These people meet, discuss the case and try to reach reconciliation through consensus. If it is not possible to reach consensus, they vote. Thus, it is clear that consensus is key on all levels, and that the primary goal is to settle the case through reconciliation, due to the fact that it is understood to ensure social peace.

It probably won’t shock you to hear that jiniology thrives in the justice system as well. Municipal women’s assemblies provide housing and education to women in their area in the form of book clubs and house calls to keep them engaged. The Asayîşa Jin work with these women’s assemblies to do safety checkups, and directly interfere in cases of patriarchal violence, child marriage, and polygamy. Separate Peace and Consensus Committees staffed entirely by women maintain safe spaces for survivors and assist with the mediation and reconciliation process.

Two kinds of prisons exist in Rojava: one for regular citizens, and one for captured ISIS fighters. Both are run by the self-administration with strict rules against private ownership, and considered an absolute last resort when the accused has to be separated from their community for safety reasons. There are also limits on how long a person can be incarcerated, and preparations made to reintegrate them. According to one interviewee, roughly 80% of incarcerated people in the municipal prisons are there because of domestic violence. On the other hand, ISIS prisons are a huge social problem in Rojava because they break down into two broad categories. Many inmates only joined ISIS in the first place because of impossible decisions made under nightmarish circumstances. Their crimes, while extreme, were also coerced — their options were to fight or die horribly. Others were the more ideological core, the “true believers” who often came to Syria from abroad. This distinction matters because the former category is potentially open to reconciliation and eventual reintegration into society. The latter would ideally be repatriated to their home countries, but the AANES is not recognized internationally, so extradition is frequently impossible.

In any case, available research suggests Rojava’s restorative justice approach has drastically reduced the prison population:

In the city of Serê Kaniyê the number of prisoners has dropped from 200 during the Assad regime time to 20 as of early 2016. Overall, there is a high rate of case resolution at the level of the Peace and Consensus Committees, which indicates wide acceptance of the new justice system by the local population. Crime rates have dropped, especially with regard to theft, and as for crimes related to patriarchal violence, the number of honor killings have declined noticeably in NES. According to the women’s organizations in NES, their work has resulted in abusive men leaving their wives. In Hilelî, Qamişlo, any man who beats his wife is socially ostracized and domestic violence seems to have vanished. In 2017 there were approximately 200 divorces, mostly due to cases of polygamy and child marriage.

In late 2020, partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic and partly due to an unsustainable influx in ISIS prisoners, the administration announced general amnesty for Syrian nationals. Per Rojava Information Center:

Those guilty of infractions and misdemeanors; the sick; and over-75s will be freed. Those guilty of serious felonies will see sentences halved, with life sentences reduced to 20 years. Convicts fleeing justice have 60 days to hand themselves in to benefit from the amnesty. Those not to be released include those guilty of: espionage and treason; honor killings; drug trafficking; commanders in terror organizations such as ISIS; and terrorists guilty of violent crimes. Low-ranking members will be released if they can provide a guarantor. Officials say the move is intended to promote a new approach to justice, revitalize community relations, and relieve pressure in prisons dealing with the strain of 10,000+ ISIS members.

The Rojavan system, democratic confederalism, is not perfect and by its very nature is always in flux. In contrast to its revolutionary ideals, the administration’s realities are morally complicated by its own self-defense against Turkish incursion, Assad forces, and ISIS. But it’s worth noting that this system, which millions of people live under to this day, can trace its intellectual provenance to American ecological and anarchist philosophy. Democratic confederalism is based in part on an idea first proposed as a way to reorganize American society around durable communities that can weather climate change. If a pluralistic society can flourish amid the unimaginable brutality of the Syrian Civil War, what might we be capable of right here at home?

Analysis: paths to restorative justice

Complementarity

So what can we take away from all this?

Earlier in this article I suggested that we cannot be idle receivers of information. If you take nothing else from this entire debrief, please, let it be this. A mutual exchange of ideas is not just a goal for today; it is not mere bloviating, and it goes well beyond soulless woke liberal politics. It is, in fact, a sturdy foundation for the only thing that can truly un-fuck our national (and international) situation.

For perhaps the majority of people listening, the COVID-19 pandemic is the first time in living memory you got the idea that our entire society might be built on sand. The engines of neoliberal capitalism were completely unprepared to respond to a disaster of this magnitude. In the months since, we’ve been watching infrastructure slowly crumble in a way not all that different from the collapse of the former Soviet Union. I personally have several friends who, already bouncing between unstable service industry jobs, completely lost the income they need to survive and faced eviction or houselessness. I also know rural small business operators to whom useless politicians passed the buck, forcing them to make an impossible choice between staying open during a global pandemic or cutting off their only way to break even and sustain their families. I am certain many of you listening can relate to this. The point is not to cast blame on this political party or that convenient scapegoat; it is instead to take a sober look across our fair land and accept that help is not coming.

But neither does it have to. We’re all we’ve got; we’re also all we need.

Another phenomenon that occurred in the wake of COVID-19 is the surge in popularity of mutual aid. Right away I want to draw a bold line for folx new to this concept. Mutual aid is very different from charity, where a relatively small group of individuals give to another group in a time of need. As a practice, there’s nothing inherently wrong with charity — lots of people are fed and sheltered by the generosity of others. Within the recipient’s life though, it tends to be a temporary fix. It is also easily co-opted by bad-faith actors. When charity is executed on a global scale by a billionaire funded nonprofit industrial complex, it propagates a specific ideology about who has influence and who ought to. This can have a devastating impact on real human lives. When vaccines emerged that could seemingly end the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation — a massively influential nonprofit — successfully lobbied against open source distribution on the grounds that it would threaten intellectual property rights.

In lieu of ideology, mutual aid is both built on and reinforced by a social ethic of complementarity. In biology this term is connected to symbiosis, the phenomenon where several organisms mutually thrive within the same ecosystem. Think of the way bees pollinate flowers and other flora, allowing the bees to eat and the flowers to reproduce. Scaled up to something like an apple tree, a much broader system of biological sustenance is achieved because other organisms (like humans) eat the fruit of those trees.

This is not just an analogy. It is the way Indigenous peoples the world over have been living for centuries, and in many of those circumstances, it is intimately tied to their conceptions of justice. We’ll revisit this later in more detail but I will note Indigenous peoples are far and away Earth’s best human land stewards, overseeing some 80% of land-based biodiversity worldwide. When you see yourself as symbiotic with the life all around you, your idea of justice will naturally adapt to that worldview.

What does this look like in practice? In northeast Syria there is a concept rooted in Kurdish tradition called hevaltî. The word roughly translates as “friendship,” but it means something altogether more profound than the generic Western understanding of that term. Northeast Syria is not just home to Kurds; it is a multi-ethnic society of up to 4.6 million people in which very different cultures must coexist. The AANES social contract acknowledges this in its opening lines:

We, the people of the Democratic Autonomous Regions of Afrin, Jazira and Kobani, a confederation of Kurds, Arabs, Syriacs, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians and Chechens, freely and solemnly declare and establish this Charter.

Speaking to the need for complementarity, the charter continues:

In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity and democracy and led by principles of equality and environmental sustainability, the Charter proclaims a new social contract, based upon mutual and peaceful coexistence and understanding between all strands of society. It protects fundamental human rights and liberties and reaffirms the peoples’ right to self-determination.

The culture of hevaltî means that among the citizens of this region there is a mutual understanding that “my community consists of my friends.” Not as some vague abstract platitude, but as a very real social category. There are things you do for your friends that you just wouldn’t do for someone you don’t feel connected to or consider your societal equal. This very simple reframing lies at the heart of the revolutions in both Chiapas and Rojava.

It is not at all a coincidence that the Zapatistas practice a remarkably similar community ethic, which they call Zapatismo. To me it underscores something so intuitive and spiritual that it’s almost too important to carry just one name. In the words of Subcomandante Marcos, the Zapatistas’ spokesperson:

Zapatismo is not an ideology, it is not a bought and paid for doctrine. It is […] an intuition. Something so open and flexible that it really occurs in all places. Zapatismo poses the question: “What is it that has excluded me?” “What is it that has isolated me?” In each place the response is different. Zapatismo simply states the question and stipulates that the response is plural, that the response is inclusive.

Think back again to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the very first things many of us naturally did was figure out who on our block was elderly or immunocompromised. We organized very simple distribution networks to make sure these people had access to basic necessities without putting themselves at risk of exposure to the virus. At the time, I lived in rural Pennsylvania across the street from a lifelong gardener well into her 80s. When I did supply drops of cat litter, dry goods, and toiletries, she gave me fresh peppers, cucumbers, and tomatoes out of her garden. As time went on the less vulnerable neighbors on my block would take turns arranging supply drops and that garden became a kind of free farmer’s market.

The culture of complementarity practiced in places like Rojava and Chiapas is extensive. It includes community members who generally suffer invisibly here in the U.S.: the houseless and convicted so-called criminals. I invite you to the idea that on the road to realizing restorative justice in Milwaukee, our first stop could be a simple — yet radical — shift in our collective thinking. We can start viewing these forgotten neighbors not as annoyances or less-fortunates to exploit for clout or virtue signaling, but as our friends.

What would you do for your friend if they were in a bind? My guess is that, whatever your answer, your first instinct is probably much closer to solidarity than to charity.

Dual Power

Mutual aid is essential, but it alone is not enough to sustain us. It is absolutely true that, in the face of disaster, small networks of people and even whole communities can and do rise up to meet each others’ needs. It is also true that when this happens, state actors tend to react like the hammer of God come to fuck up their Christmas.

There is a vast body of sociological research to support this. One seminal work is Elites and Panic: More to Fear than Fear Itself, a 2008 analysis documenting a phenomenon the authors dub elite panic. To quote the paper’s introduction:

Sociological research on how people respond to disasters has been going on for more than 50 years. From that research comes one of the most robust conclusions in sociology: panic is rare. There is detailed research on supper club fires, airplane crashes, epidemics, hurricanes and so on. Regardless of whether the hazard is dramatic or mundane, whether there is a low or high body-count, or whether the threat is acute or chronic, social scientists agree that “panic” explains little that is important about how people, in collectives, respond to disaster.

Panic from below is extraordinarily rare. From the great San Francisco fire of 1906, to the behavior of Londoners during the blitz, to New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina — when the chips are truly down, communities of people tend to respond by organizing rudimentary distribution networks and other mutual aid. Mass hysteria, B-movie style pandemonium in the streets, is all but unheard of. What is extremely common is panic from above: elites and authority figures, including elected politicians and business tycoons, reflexively pulling the levers of state power to assert their dominance. This is hardly a shock in the early half of 2022, after 24 months of a global pandemic has stranded vast groups of people without any substantive safety net. Violent police riots have routinely followed even the mildest forms of antiracist dissent, while fascist street gangs openly invade liberal enclaves like Los Angeles and Portland without any hint of law enforcement response. On a completely unrelated note, a Business Insider article from October 2020 found that American billionaires had grown their personal wealth by more than 637 billion dollars since January of the same year.

Politicians and the ultra-wealthy, nominally our society’s decision makers who have access to extraordinary resources and incomprehensibly vast oceans of data, ultimately tend to prioritize threats to their power, influence, and public reputation while everyone else worries about the survival of their neighborhood. Their decisions are not the only, or even the most important, ones that need to be made. The author Cory Doctorow, in analyzing Rebecca Solnit’s essential work A Paradise Built in Hell, summarizes the situation this way:

Elites tend to believe in a venal, selfish, and essentially monstrous version of human nature, which I sometimes think is their own human nature. I mean, people don’t become incredibly wealthy and powerful by being angelic, necessarily. They believe that only their power keeps the rest of us in line and that when it somehow shrinks away, our seething violence will rise to the surface — that was very clear in Katrina. Timothy Garton Ash and Maureen Dowd and all these other people immediately jumped on the bandwagon and started writing commentaries based on the assumption that the rumors of mass violence during Katrina were true. A lot of people have never understood that the rumors were dispelled and that those things didn’t actually happen; it’s tragic.

It’s worth asking, loudly, why this happens. There are as many answers to this question as there are politicians, and each of those answers is complex and sociologically fascinating. For our purposes, what’s important is that it definitely is not the result of some vague grand conspiracy. Power is an exceptionally potent drug even in mild doses and there has been no human being, living or dead, immune to its effects. What we are dealing with is not some loosely defined notion of evil, and none of this is meant as an excuse to make value judgments against individual people. Elite panic and the drug of power are both deeply rooted in the human psyche, much like a hedgerow. We will never be rid of them, but we can do a better job of balancing them with other human tendencies — like egalitarianism. I’m lingering on this point because the death of nuance is a huge part of how we all got into our current mess. In a media environment built so fundamentally and for so long on outrage, cynicism is an especially easy trap. It can lead to dehumanization of the political “other,” which desensitizes us to violence. It works to raise our national temperature closer to a boiling point. It’s also an essential ingredient in kicking off modern civil conflicts.

I invite you to the idea that a much more fruitful alternative is to build durable networks of solidarity, and it’s here that I have to lay my cards on the table. The lessons I’m curating from both Chiapas and Rojava are overwhelmingly focused more on social ethics than on ideology, and that is very much in the spirit of both revolutions. Because to be blunt, human beings will never share a single ideology and it would be unspeakably, foolishly arrogant to try to impose one. Ideological pissing contests are a path to cynicism which is a precondition for violence. Notwithstanding the direct cost in human lives, a modern style civil war in North America would utterly devastate the entire planet. The U.S. is the source of much of the world’s agriculture, controls an awful lot of its wealth, and, not for nothing, is littered with just an absolute shitload of nuclear weapons. The American military is also the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gasses and would only fart out even more during a civil conflict scenario. I believe I’ve made my point: long-term sustainability is no less central to our goals here than restorative justice, especially if part of what we’re restoring is ecological balance.

In truth, every democratic system should implicitly expect and accept both disagreement and a certain lack of closure, sometimes bitterly so. The modern United States is home to no less diverse a society than Syrian Kurdistan, regardless of the lens you view it through: ethnically, politically, spiritually, sexually, and geographically, there are some 300 million ways and counting to be an American. And make no mistake, democracy is exactly the goal — neither a liberal nor representative one, nor a system of pointlessly bureaucratic popularity contests, nor a spooky shadow government come to take your guns and your freedom — but a direct democracy, a society truly run from below by its people. To quote the American philosopher Murray Bookchin, in a piece that directly inspired democratic confederalism:

It is an effort to work from latent or incipient democratic possibilities toward a radically new configuration of society itself–a communitarian society oriented toward meeting human needs, responding to ecological imperatives, and developing a new ethics based on sharing and cooperation. That it involves a consistently independent form of politics is a truism. More important, it involves a redefinition of politics, a return to the word’s original Greek meaning as the management of the community or polis by means of direct face-to-face assemblies of the people in the formulation of public policy and based on an ethics of complementarity and solidarity.

Building a direct democracy is the project of dual power. In both Chiapas and Rojava, direct assemblies are formed from below starting at the household level. A network of individuals forms a household assembly, a network of households forms a neighborhood assembly, a network of neighborhoods forms a municipal assembly, and so on. Rather than elect representatives, folx generally take turns acting as delegates to churn the engines of decision making themselves. Day-to-day life is not centered around work, at least not in the way you’re probably thinking. The goal is not to service the whims of a middle manager with less experience than you or to stuff the pockets of some rich asshole you’ll never meet who lives in a city you’ll never visit. Your access to housing and healthcare does not depend on capricious dipshits who only bother to talk to you when they can exploit you. In these autonomous administrations, day-to-day life is generally structured around the people in your community: your neighbors, your family, the people you see when you’re out at the store or spending a day at the beach, the people who care for your kids and remember the names of your pets.

It’s not perfect because people aren’t perfect. But right now, as you read this, socially conservative Arab farmers in the Euphrates Region are peacefully coexisting with city dwellers in places like Qamişlo. Councils of neighborhood grandmas are brokering peace between survivors and perpetrators of violence. Women across northeast Syria are reinterpreting whole fields of study to liberate each other from their most ancient oppressor. Many are co-leaders in the SDF, defending their neighbors against the cancerous ideas at the heart of both ISIS and advancing Turkish fascists.

Dual power, an American version of Zapatismo, is the best chance we have of realizing similar autonomy right here at home in raw human defiance of the crises of our age. Its aim is to build up a new world within the crumbling shell of the old. It presents a strategy in which mutual aid infrastructure for a social revolution from below is laid peacefully and in cooperation between rural and urban localities, between conservative and progressive attitudes. It will naturally oppose the crumbling state because the crumbling state rightly sees mutual aid as a serious threat to its influence, and its bottom line. But opposing the state is not really the point of dual power. Self-determination is.

So how do we do this? How can a project of mutual aid expand nationwide while remaining fundamentally local, nimble, and decentralized? How can a dual power approach solve more complex infrastructure problems, like food and medicine distribution or public education? What sort of justice system are we going to replace police and prisons with? Coupled with that, how will we administer mental health assistance to those who need it, when they need it? How can we accomplish all this and more without replicating, through sheer force of habit, the exact problems we’re trying to fix? Will there be violins? Who’s going to make the violins? There do exist multiple proposed solutions to all of these problems, but at the end of the day, it’s for all of us to come together to decide.

That sums up our first goal and our first call to action: to build cultural infrastructure for autonomous decision making, which gets us on the path to physical infrastructure for material needs. The coming episodes will feature interviews from people involved in these movements in an attempt to learn and apply their methods. We will also hear from local organizers who are already forging viable paths. It’s starting small, but the problems we face are manageable if we break them down into person-sized parts.

And I don’t know about you. But after the last few weeks – the last few years – of relentless bad news, I could sure as shit use a community.

Endnotes

This article was written while being sustained first by land and freshwater sources in occupied Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe territory, and later on Lenape and Erie land.

I mentioned earlier that lack of international recognition presents a major problem repatriating ISIS combatants held in Rojava. It also presents problems for COVID-19 vaccine distribution, water and food distribution, and defense against Russia-backed Turkish incursion. There are things you can do to help with this: contact your representatives and express support for recognizing the AANES as an autonomous government. To learn more please see the Rojava Must Survive campaign.